The Legal Immigration Family Equity (LIFE) Act and LIFE Act Amendments of 2000 were passed to allow certain aliens present in the United States who were beneficiaries or derivative beneficiaries of immigrant petitions to adjust status even though they would otherwise be forbidden to do so.

Second 245(i) was originally enacted in 1994 (HR 4603, Pub. Law. 103-317), then terminated in 1997, then temporarily revived with the LIFE Act of 2000. Although the LIFE Act and Section 245(i) are old laws, they powerfully affect many people today. Normally, INA 245(a) prohibits adjustment of status for an alien who entered the United States without permission, and INA 245(c) prohibits adjustment of status for those who violated their status, except for the spouse, parent and minor child of a US citizen. That means absent 245(i) eligibility, those who entered without permission or violated status have to leave the United States to apply for permanent residence.

The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) imposes severe penalties on aliens who remain in the United States unlawfully and then depart. If those aliens are ineligible to adjust status, absent 245(i) or a waiver, they may not enter the United States with an immigrant visa until they have lived abroad for as long as ten years. It is upon leaving that the serious penalties of IIRIRA arise.

What 245(i) Does and Does Not Do

245(i) allows a person to adjust status even if he:

- Entered without inspection

- Overstayed an authorized period of stay, or

- Worked without authorization

245(i) does not do anything else. It does not waive any other grounds of inadmissibility, cure other types of status violations, or confer any other benefits at all.

Applicants who entered unlawfully, overstayed and worked without authorization may adjust status if they qualify for 245(i). Because serious penalties arise when a person who accrued 180 days or more of unlawful presence departs the United States, 245(i) is a crucial benefit for many applicants.

245(i) allows qualifying aliens to avoid being subject to the unlawful presence bars because they can adjust status without departing the US. But what about someone who is already subject to the three year, ten year, or permanent bar? At this time, courts hold that 245(i) does not cure or waive any of the unlawful presence bars.

The Board of Immigration Appeals decided in 2007 that 245(i) does not waive the permanent bar for unlawful presence found at 212(a)(9)(C)(i)(I). Matter of Briones, 24 I.&N. Dec. 355 (BIA 2007). The Ninth Circuit had previously held in 2006 that 245(i) does apply to aliens inadmissibile under even the permanent bar at 212(a)(9)(C)(i)(I). Acosta v. Gonzalez, 439 F.3d 550 (9th Cir. 2006), but the court later revisited the decision and overruled it. Garfias-Rodriguez v. Holder, (9th Cir. 2011).

The 245(i) Rights of Principal Beneficiaries

The LIFE Act is straightforward if you are a principal beneficiary. A principal beneficiary is the specific beneficiary for whom a visa petition is filed (for example when your spouse, child, parent, brother or sister files a petition for you with your name listed as the beneficiary, you are the principal beneficiary). When you see the word "beneficiary" it means principal beneficiary. You are a "grandfathered" 245(i) principal beneficiary and may qualify to adjust status to permanent resident using 245(i) if you:

- Are the beneficiary of an I-130 or I-140 petition filed on or before 04/30/2001

- Are the beneficiary of a labor certification filed on or before 04/30/2001

- Were physically present in the United States on 12/21/2000 if you are the principal beneficiary and the petition was filed between 01/15/1998 and 04/30/2001

- Are currently the beneficiary of a qualifying immigrant petition (either the original I-130 or I-140 or a later filed immigrant petition)

- Have a visa number immediately available to you

- Are admissible to the United States

This means that if you are the principal beneficiary of an immigrant petition or labor certification application filed on or before 04/30/2001, you may adjust status later even if you seek to adjust status based on a petition filed by a different person or company. The regulations discuss 245(i) grandfathered principal beneficiaries at 8 CFR 245.10.

It is not necessary that the petition filed for you on or before 04/30/2001 was approved, or that you pursued it. It is only necessary that it was properly filed and approvable when filed. Properly filed means that it was filed with the proper filing fee and signed petition forms and either received by INS on or before April 30, 2001, or if mailed, postmarked no later than April 30, 2001. 8 CFR 245.10(a)(2)(i). Approvable when filed means that the petitioner and beneficiary qualified at the time the petition was filed and it was a bona fide and meritorious in fact, and not a fraudulent or frivolous petition. 8 CFR 245.10(a)(3). But you still may qualify even if the petition was later denied or abandoned.

Physical Presence

245(i) was enacted in a 1995 law that provided an unlawful entry waiver for those who were the beneficiaries of petitions or labor certification applications filed on or after October 1, 1994. IIRIRA set a deadline of 245(i) eligibility to petitions filed no later than January 14, 1998. In 2000, Congress passed the LIFE Act extending 245(i) eligibility for petitions filed up through April 30, 2001 provided that the petition or labor certification's beneficiary was physically present in the United States on December 21, 2000. Aliens seeking to adjust status based on a petition or labor certification filed between October 1, 1994 and January 14, 1998 do not have to document their physical presence in the United States on December 21, 2000. But those who are the beneficiaries of petitions or labor certifications filed between after January 14, 1998 and up until April 30, 2001 must demonstrate their physical presence in the United States on December 21, 2000 to qualify for 245(i) protection. Derivative beneficiaries like the primary beneficiary's spouse and minor children do not have to demonstrate physical presence in the United States on December 21, 2000 to qualify for 245(i) benefits even if the primary beneficiary does need to prove physical presence. USCIS issued a memo on January 26, 2001 addressing adjustment of status under 245(i) and the various physical presence proof requirements based on the underlying petition or labor certification and whether the beneficiary is a primary or derivative one. Click here to read the USCIS 245(i) memo dated January 26, 2001.

The 245(i) Rights of Derivative Beneficiaries

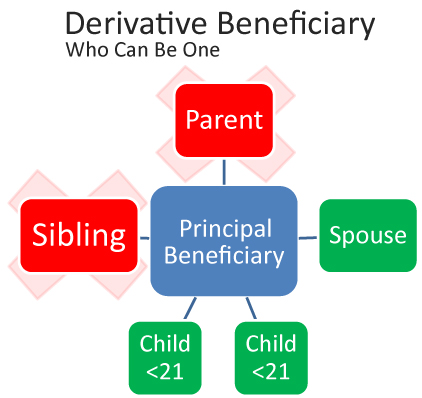

Derivative beneficiaries are a little more complicated. First, a derivative beneficiary is the spouse or unmarried minor child of a principal beneficiary who the petitioner could not file a petition for directly. If the person who petitioned for the principal beneficiary could have filed a petition for you, you cannot be a derivative beneficiary.

"Grandfathered" Derivative Beneficiaries

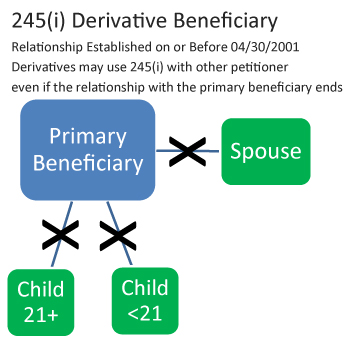

USCIS uses the term "grandfathered" derivative beneficiary to describe a person who:

- Is or was a derivative beneficiary, and

- The relationship creating that status existed on or before 04/30/2001

If a spouse was married to a principal beneficiary on or before April 30, 2001 or a stepchild relationship was created by a marriage that occurred on or before 04/30/2001 and the principal beneficiary is 245(i) eligible, the derivative beneficiaries are "grandfathered."

For an alien to qualify under 245(i) as a derivative grandfathered alien, the principal alien must satisfy the requirements for grandfathering including the physical presence requirements under INA 245(i)(1)(C). Matter of Ilic, 25 I.&N. 717 (2012).

What do you win if you're grandfathered? Grandfathered derivative beneficiaries may keep their 245(i) benefits even if the relationship that created their derivative status ends, for example through divorce. A grandfathered derivative beneficiary has the right to adjust status based on any immigrant petition and any lawful basis without regard to whether the principal beneficiary adjusts status or has the same relationship to her at the time she applies to adjust status.

The spouse, parent and child of a grandfathered derivative beneficiary is not grandfathered and do not qualify in any way for benefits under 245(i). Matter of Legaspi, 25 I.&N. 328 (2010).

Derivative Beneficiaries Who Are Not

"Grandfathered"

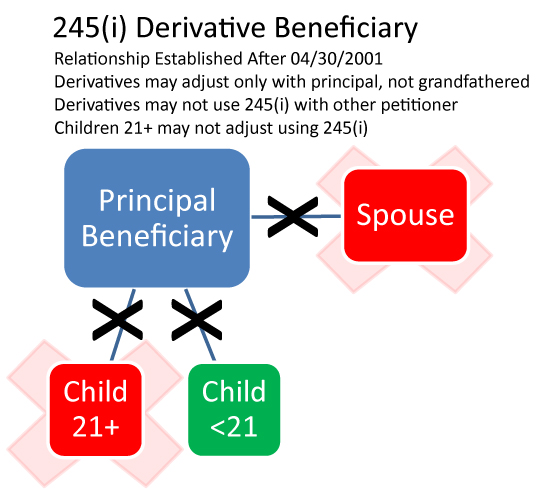

A derivative beneficiary is not grandfathered if the relationship that gave rise to derivative status was created after April 30, 2001. For example, a spouse who married a 245(i) eligible beneficiary after April 30, 2001 is not grandfathered.

Is there any benefit to being a derivative beneficiary of 245(i) who is not "grandfathered?" Yes, derivatives who aren't grandfathered may still use 245(i) to adjust status, but only as the dependent of the principal beneficiary. If the derivative beneficiary who is not grandfathered applies to adjust status as the dependent of the wife, or stepfather (for example) who was the relation that created the applicant's derivative status, the derivative beneficiary may adjust status using 245(i).

But if a derivative beneficiary is not grandfathered, he may not apply to adjust status through any other petition or legal basis for adjusting status. A derivative beneficiary who is not grandfathered may not adjust based on a petition filed directly for her. For example, if a foreign national is the beneficiary of a petition filed by his brother on or before April 30, 2001 and after April 30, 2001, he married a person illegally present in the United States, the wife can adjust status as the husband's derivative and at the same time as he does. But if the couple has a US citizen child over the age of 21 who petitions for both parents, the husband who is grandfathered may enjoy 245(i) benefits arising from the petition filed by his brother on or before April 30, 2001, but his wife may not adjust status as the direct beneficiary of the son's petition because she is not a grandfathered derivative beneficiary of her husband's brother's petition. She can, however adjust status as the derivative beneficiary of her husband if her husband adjusts as the direct beneficiary of his brother's petition. For more information about derivative beneficiary adjustment issues, see the USCIS memo Clarification of Certain Eligibility Requirements Pertaining to an Application to Adjust Status under Section 245(i) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, March 9, 2005.

When the Petition Was Defectively Filed

For a beneficiary or derivative beneficiary to be eligible for 245(i) benefits, the petition or application must have been "filed" on or before April 30, 2001. Generally the regulations provide that a petition or application is "filed" when USCIS or Department of Labor receives the application or petition, signed where required and with the proper filing fee. USCIS made a different regulation for 245(i) cases because of the large volume and difficulties that courier services and the US Postal Service may have had timely delivering so many packages. USCIS decided that petitions and applications were properly filed for the purpose of 245(i) if they were (1) received by INS on or before April 30, 2001, or (2) if submitted by mail, the mailing was postmarked on or before April 30, 2001. 8 CFR 245.10(a)(2).

USCIS has held that an improper filing fee, or unsigned filing fee check renders a petition or application not "properly filed" when received. However, in Blanco v. Holder, 572 F.3d 780 (9th Cir 2009), the Ninth Circuit held that a beneficiary was eligible for § 245(i) benefits based on a petition submitted before April 30, 2001 but rejected as untimely because the lawyer's filing fee check was not signed. The court held that because a bank will sometimes negotiate an unsigned check, INS could have presented the unsigned check to the bank and allowed it to determine whether to negotiate it.

The First Circuit has held the contrary that a family-based I-130 petition was not timely filed before the April 30, 2001 deadline for § 245(i) because the money order for the filing fee was unsigned. McCreath v. Holder, 573 F.3d 38 (1st Cir 2009)